From vaccine manufacturing to gene therapy vector production, cell factories are driving cell culture from laboratory scale toward true industrialization. Within this transition, seeding density often serves as the first critical checkpoint for success.

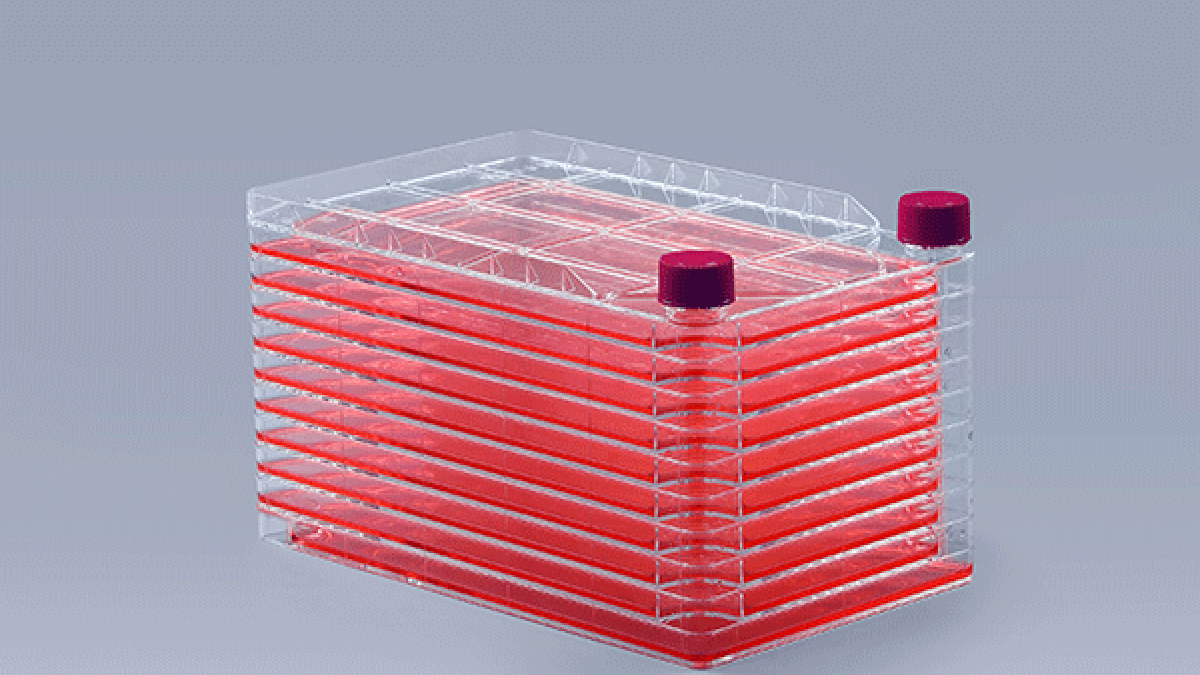

In biopharmaceutical cleanrooms, the seeding process within a cell factory is often quiet yet intense. Technicians stand at the workbench, carefully introducing counted and quality-verified cells into multilayer culture systems. For a 40-layer cell factory, this step is not only the starting point of the operation—it directly determines the success of the cultivation process over the days or even weeks that follow.

Among all culture parameters, seeding density is one of the most easily underestimated yet most difficult variables to control with precision.

Seeding Density: Not Simply “The More, the Better”

At its core, seeding density represents a balance between cellular growth potential and the carrying capacity of the culture environment. Taking HEK293 cells as an example, practical experience shows that an initial density of approximately 3 × 10⁴ cells/cm² is commonly applied under single-layer cell factory conditions or equivalent culture areas. This value is not arbitrary, but rather the result of extensive experimental validation.

If the seeding density is too low, insufficient paracrine signaling between cells can lead to poor attachment efficiency and delayed proliferation. Conversely, an excessively high density may rapidly deplete nutrients and cause early accumulation of metabolic byproducts, ultimately suppressing further growth.

In multilayer cell factories, these effects are often amplified. As the number of layers increases, gas exchange efficiency and dissolved oxygen gradients change accordingly. Therefore, it is common practice to reduce the baseline single-layer seeding density by 5–10% to prevent growth limitation in the lower layers at an early stage.

Different Cell Lines, Different Density Tolerances

There is no universal seeding density suitable for all cell lines. Different cells exhibit markedly different responses to initial density conditions.

For example, CHO cells often favor relatively lower initial densities to support stable antibody expression, whereas overly dense seeding may negatively affect expression consistency. In contrast, fibroblast cell lines such as MRC-5 require a higher degree of cell-to-cell contact to initiate optimal proliferation.

These differences arise from variations in growth factor dependency, contact inhibition thresholds, and metabolic rates. Mature process development does not rely solely on published literature values, but instead establishes validated density ranges tailored to specific cell lines. Experienced process engineers are typically well acquainted with these distinct “cell behaviors.”

From Culture Flasks to Cell Factories: Density Scaling Is Not a Simple Area Conversion

During process scale-up, seeding density calculation is a common source of error. Directly scaling cell numbers from T-flasks or standard culture vessels to multilayer cell factories based solely on surface area often leads to unpredictable outcomes.

The structural characteristics of multilayer cell factories alter fluid dynamics and gas diffusion pathways within the culture system. In practice, when transitioning from T-175 flasks to 5-layer or higher-layer cell factories, it is often necessary to increase the seeding amount by approximately 15–20% beyond the theoretical area-based calculation. This adjustment helps compensate for differences in oxygen availability and mass transfer efficiency in deeper culture layers.

For this reason, established biopharmaceutical manufacturers typically develop dedicated seeding parameter matrices for specific combinations of cell line × layer number × culture conditions. These datasets represent a core component of proprietary process know-how.

Dynamic Density Optimization: Combining Data with Experience

In real production settings, seeding density is rarely treated as a fixed parameter. Experienced operators continuously refine density settings based on growth trends observed over previous passages.

If cells enter the plateau phase earlier than expected, the initial seeding density is reduced in subsequent batches. Conversely, if a prolonged lag phase is observed, the seeding amount may be increased by approximately 5% to accelerate culture initiation. This data-driven, adaptive approach ensures that cells consistently enter the production phase under near-optimal physiological conditions, while minimizing batch-to-batch variability.

Conclusion: The First Step Toward Successful Scale-Up

From vaccine manufacturing to gene therapy vector production, cell factories are driving cell culture from laboratory scale toward true industrialization. Within this transition, seeding density often serves as the first critical checkpoint for success.

It requires both robust data and a deep understanding of cell behavior. Even minor adjustments in seeding density can significantly impact final yield, quality consistency, and overall process reproducibility. These carefully calculated and repeatedly validated details form the foundation upon which modern large-scale biopharmaceutical production is built.